We are still making one big nail

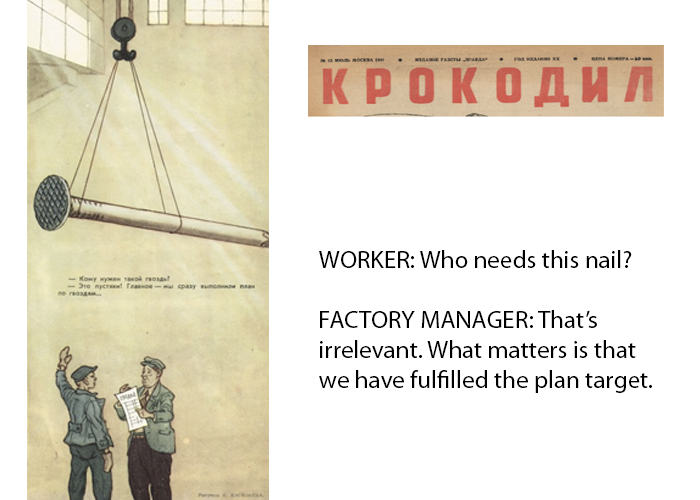

I’m old enough that socialist planning was on my undergraduate curriculum, writing essays on its success and failures. One of the issue in central planning was the ‘one big nail problem’ named after a cartoon that appeared in the Soviet magazine Krokodil in 1957. Planning requires the planners set output targets for factories across the country. So, for example, a nail factory might be required to produce a given tonnage of nails each quarter. This target might be most easily met by making simply one big nail. It meets the target, but it’s useless.

Whilst we might laugh at the Soviet planners, the one big nail problem stays with us with the use of performance targets. I wrote in my last blog about the problem of using outcome measures in order to measure impact. The use of both output and outcome targets also can be problematic when used to manage the delivery of social and economic programmes.

An example was highlighted earlier this year by the British satirical current affairs magazine Private Eye. Under the UK’s Shared Rural Network programme the target is to provide 4G coverage for 95% of the country. That is defined as 95% of the geographical area, not 95% of the people. This has led to companies building telecoms masts on cheap land in remote areas in Scotland, which provide coverage to exactly zero people. This helps meeting the target and providing mobile coverage to passing deer and the odd sheep. But it does nothing towards increasing coverage for people. It meets the target, but it’s useless.

This is an extreme example. The problems in the use performance targets emerge in many areas of public policy. Another example comes from youth training programmes, where so-called “creaming” is an issue. Creaming refers to the practice of recruiting those who are easiest to recruit, rather than the more disadvantaged for whom the course is intended (an issue which has also been documented by Private Eye). The most disadvantaged are young people who are not in education and employment or training, so-called NEETs. These young people often have complex problems coming from difficult backgrounds and weak educational attainment, with teachers and others who have given up on assisting them to achieve their potential. Such young people to harder to reach and engage and so training providers, who are paid per participant, reach out to those who are less problematic and less in need of assistance.

There is not an easy answer to this problem. I am not proposing to abolish the use of performance targets. To the contrary, I have long been a proponent of their use, long before “output-based aid”, payment by results, and social impact bonds became a thing. But it is clear that we do need to take performance measures more seriously to measure if the right actions are being taken.

Part of the solution can be requiring more accurate or more complete data on programme participants rather than simply head counting. This is, of course, an additional administrative burden for implementers and young people, which may be a barrier to participation. Part of solution can also be a qualitative monitoring system. Qualitative monitoring is often mentioned, but far less done. Combining the collection of participant data with an entry interview to understand the young person’s skills, aspirations and constraints will help both management and monitoring. It is more work, and so more cost. But there is a cost to not using meaningful targets. It is the cost of building telecoms masts where they reach no one. It is the cost of providing training to those who don’t need it. It is the cost of producing the useless one big nail. And it is the cost of squandered youth and missed opportunities for those most in need when training providers don’t include them.