Biodiversity and Sustainable Development: The Agenda for Science and Policy

This article was originally published on GlobalDev. Read it in français and Español.

The threat of climate change to development is now widely understood: less recognized is the impact of the biodiversity crisis. The 2023 Global Development Conference shone a light on the ecological basis of our economies, livelihoods and well-being, and illustrated how effective collaboration between different sectors of society is essential to finding “nature-positive” solutions for sustainable development.

“Truly sustainable economic growth and development means recognising that our long-term prosperity relies on rebalancing our demand of nature’s goods and services with its capacity to supply them. It also means accounting fully for the impact of our interactions with Nature across all levels of society.”

With these powerful words, Partha Dasgupta of the University of Cambridge launched his independent review of the economics of biodiversity, commissioned by the UK Government and published in 2021. In a similar way to the Stern Review of 15 years earlier, which warned of the costs of inaction on climate change, Dasgupta’s final report explores the dangers of biodiversity loss – declines in the variety and abundance of species and ecosystems – and what can be done to preserve the ecological underpinnings of our economies, livelihoods and well-being.

The Dasgupta Review was published before the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP15) to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity in December 2022, which culminated in a new international agreement. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), agreed at COP15, spells out a plan to preserve nature and make sure it is a long-term engine of jobs and growth that also reduces carbon emissions. Key commitments include, by 2030, to:

- Protect 30% of the Earth’s lands, oceans, coastal areas and inland waters – the ‘30x30’ aspiration

- Reduce the annual government subsidies that encourage environmentally wasteful activities by $500 billion

- Cut food waste by half

The 2023 Global Development Conference organized by the Global Development Network (GDN) focused on what these ambitions mean for public policy, business practices and civil society. The meeting, which brought together researchers, policymakers and practitioners from diverse backgrounds around the world, especially the Global South, was organized with Future Earth and hosted by the Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Ecuador. This location felt particularly appropriate given Ecuador’s status as one of the world’s megadiverse countries – those that harbour the majority of the Earth’s species and a high number of which are endemic.

The Challenge of Biodiversity Loss for Development

The Earth is experiencing a dangerous decline in nature as a result of human activity. According to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), one million species of flora and fauna – almost a quarter of the global total – are threatened with extinction due to deforestation, habitat loss, overexploitation, pollution and climate change.

This loss of biodiversity has far-reaching consequences, including the disruption of ecosystem services, such as pollination, soil regeneration and carbon sequestration, which are critical for human well-being.

But a change of direction is possible. As Odile Conchou of the Agence Française de Développement said in opening one of the conference plenaries, the GBF has set the path to “a world living in harmony with nature by 2050” and now it is time to act. That requires local, national and global cooperation among public policymakers, the private sector and civil society.

Adequate financing is essential to ensure protection of biodiversity, conservation of ecosystems and to avoid excessive depletion of natural capital (the world’s stock of natural assets). It is also critical for the alignment of these goals with the other objectives of sustainable development: tackling poverty, inequality and climate change.

Poverty, Inequality and Sustainable Development

Several conference sessions focused on the links and possible trade-offs between biodiversity loss, climate change, poverty and global inequality. For example, Luciano Andriamaro of Conservation International, Madagascar, noted that many communities depend on the ecosystem services which are being altered by the climate crisis, and that resource exploitation is also causing biodiversity loss. And Deshni Pillay of the South African National Biodiversity Institute looked at the benefits of maintaining her country’s ecological infrastructures, which have the potential to create jobs and improve food and water security.

Independent consultant, Ivan Borja described the need to raise agricultural productivity in Ecuador. This will not only increase farmers’ incomes, but also discourage the further loss of natural forests that harms both the climate and biodiversity. Hajer Kratou of Ajman University took a more macro perspective, exploring the effects of biodiversity loss on inequality in 60 countries over a 25-year period. Her analysis confirms the devastating impact of deforestation on the access to food and water for the most vulnerable communities.

Food systems and the balance between production and conservation were discussed at length during the conference, including in a conversation between Jyotsna Puri of the International Fund for Agricultural Development and Elena Lazos Chavero of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico. They emphasized the importance of putting biodiversity concerns at the heart of the agriculture and fisheries sectors and, in particular, the need to address the one-third of food production that goes to waste, largely in the Global North. There are difficult issues here around ownership of land and production, when one-third of food is produced by smallholders and the rest by transnational corporations.

Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities

Another recurring theme at the conference was the importance of working with local communities, including indigenous people who constitute 5% of the world’s population but live in the places that encompass 80% of the world’s biodiversity. Girma Kelboro Mensuro of the University of Bonn argued that in the tropics, people and nature “belong together” and interact more closely. For indigenous communities, he explained, biodiversity is more than a source of resources: it is also their history and belonging – ”culture defines nature and nature affects culture”.

How to respond in terms of policy-making is a challenge. Laila Thomaz Sandroni of the Inter-American Institute for Global Change Research pointed out that although ‘indigenous peoples and local communities’ are cited 16 times in the GBF, their inclusion is based in policies that are often led by other actors and institutions. The framework, she added, reflects increasing awareness, but it does not contemplate entirely changing pre-existing power asymmetries: the main instruments to protect 30x30 are the same ones that have produced injustices in the past.

Marla Emery, co-chair of the IPBES assessment report on the sustainable use of wild species, cited an example of the potential conflicts between scientific solutions to environmental threats, and the livelihoods of indigenous peoples. Wind turbines built in Norway on the ancestral lands of the Sami people have become a huge controversy, setting demand for renewable energy against the rights of reindeer herders to preserve their culture.

Targets and Measurement

Among the GBF’s key elements are four goals for 2050 and 23 targets for 2030. In world affairs, these now sit alongside the net-zero commitments of the Paris Agreement on climate change, and the 169 targets of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Whether such targets are an effective way to make change happen was heavily debated at the conference. The balance of opinion seemed to be that they are a ”necessary evil”. Vanessa Ushie of the African Development Bank suggested that they enable a global coordination effort: “we need more research, knowledge and engagement from different actors in society, and integrated targets might help the private sector to understand”.

Plenty of other systems of measurement might also prove useful for addressing biodiversity loss. One is the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Global Ecosystem Typology, which aims to identify the ecosystems that are most critical for biodiversity conservation, research, management and human well-being. Another, introduced by Alison Fairbrass of the University College London, assesses countries’ performance on “‘strong environmental sustainability” . This measure is based on scientific standards that represent the situation at which natural capital can maintain its functions over time.

An overarching theme of discussions around all these targets and measures was the need to address a continued failure to value nature in a way that has a real impact on human behaviour. As an August 2023 article in Nature began, “Twenty-five years since foundational publications on valuing ecosystem services for human well-being, addressing the global biodiversity crisis still implies confronting barriers to incorporating nature’s diverse values into decision-making.”

This problem was central to Partha Dasgupta’s review. He argued that gross domestic product is no longer fit for purpose when it comes to judging the economic health of nations. It is, he concluded, based on a faulty application of economics that does not include depreciation of assets, such as the degradation of the biosphere.

At the conference, Simon Levin of Princeton University and Dasgupta’s co-author of a recent study of economic factors underpinning biodiversity loss, talked about ”inclusive wealth”. This concept encompasses not just physical and human capital but natural capital too. And it not only considers natural capital’s total stock, but also its distribution across humanity – while recognising that ”we are embedded in Nature”. It can be used to identify the institutional reforms that need to be introduced to manage global public goods, such as the oceans, the atmosphere and tropical rainforests.

Dasgupta and Levin’s conclusion serves as a call to action: ”Humanity’s embeddedness in Nature has far-reaching implications for the way we should view human activities – in households, communities, nations, and the world.” It was a theme that echoed throughout the conference and in the closing remarks by GDN president, Jean-Louis Arcand.

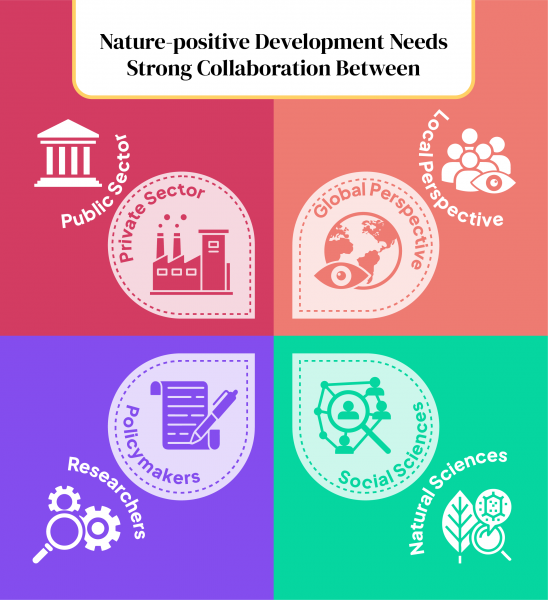

Arcand urged continued collaboration to achieve “nature-positive” development. This has to happen at all levels: between the public and private sectors, local and global perspectives, the natural and social sciences, and between researchers and policy-makers.